Betsy is giving a tour of her home in the Old Knitting Factory on Sunday at noon Eastern/5 p.m. Central European Time this Sunday during Indie Across the Pond. The tour is included in your Indie Across the Pond registration.

Last spring, I fell in love with an old Irish knitting factory. Now I’m living in it with my toddler, slowly renovating this tumbledown property and running a crowdfund to turn it into a childcare-inclusive arts residency for other single moms like me. I’ve been a knitter all my life, but I never could have guessed that knitting would become the foundation of my life and my home in such a literal way.

Ever since leaving an abusive marriage, home ownership has been a fantasy of mine, but it’s felt like a purely fantastic one for someone like me: a single parent, largely self-employed, an immigrant to Ireland. My son and I had gone from a domestic violence shelter to a hotel to a friend’s guest room and finally to a tiny bungalow where I struggled to make rent each month. Still, step by tiny step, I dreamed of something better. A place where we could feel safe, and could rest. A home.

That dream turned into a plan one day in 2018, when my friend Joan and I made our annual pilgrimage to the Knitting and Stitching Show in Dublin, a smorgasbord of yarn and fabric suppliers, craft demonstrations, and textile art exhibits. I’d spent much of our train ride to the city scrolling through unattainable real-estate listings on my phone and sighing dreamily.

Joan, 30 years my senior and eminently practical, rolled her eyes at my flimsy imaginings. “If you want to buy a house, there are ways to make it happen,” she said. “You’re a writer. Why not write about a house, and sell the book to buy it? You know, Under the Tuscan Sun and all that?”

It’s true: I’ve published five novels and many essays, and I teach writing at the National University of Ireland and at retreats in Kylemore Abbey. And, as I tell my writing students, sometimes clichés exist for a reason. My heart skipped an actual beat at Joan’s words. I felt it stutter.

I could write a book to buy a house.

“Joan,” I cried, plunging into cliché-land wholeheartedly, “that’s just crazy enough to work!”

I felt more energized rummaging through yarn and making plans that day than I had in months of sleepless, toddler-broken nights, or endless days working multiple jobs. On the train home from Galway, I wasn’t looking at real estate listings. I was knitting, and I was writing.

It’s taken me a long time to find the right building for my dream-turned-plan, though: the first few places I pitched the idea to had no interest in a single mom who would have to rent at first while I crowdfunded and saved and wrote my book. I could hardly blame them for that, but I couldn’t give up dreaming, either.

And like my child, my dream was growing all the while: I didn’t want just a home for myself and my son, I realized, but a place where I could offer the rest and safety I craved to other single moms who struggle to find space for creative work between parenting and paying the bills. I’d joined the survivors’ group at my local shelter, and those women inspired me and restored so much of my lost faith in myself. I saw through them that single mothers are worthy of being, not stigmatized, but celebrated. A childcare-inclusive residency became an intrinsic part of my plan; but it also made it even harder to find a property that would work.

And then, one sleepless night in March, I saw the Old Knitting Factory. The name, of course, called to me first: I had always loved to knit, and the plan to make my domestic dreams come true had been born at the Knitting Show.

The listing showed a long white-and-yellow house nestled on the rugged, overgrown shore of a Connemara lake. Built in 1906, it was a 114-year-old mess: full of crumbling paint and peeling vinyl floors, a leaky roof, and a cinderblock-lined backyard that had come straight from the dank armpit of the seventies. It had first been built, the listing said, to teach rural women knitting skills that they could use to support themselves financially.

A house built to foster women’s independence. A place that had been centered on my favorite craft since its beginning, and that had been reincarnated several times already: as the first Irish-language cinema in the 1970s, and later as a jewelry-making studio. For the last several years, it had been a little-used vacation home, and parts of it were well-nigh falling down.

But mending, I realized, had been part of my dream all along. Like turning a long piece of string into a sweater that can keep you warm, I wanted to remake this tumbledown old factory into a source of warmth and care, not only for my own little two-person family, but for other single mothers who had walked the path that I’d found both so freeing and so hard.

I wrote to the owner, telling him all my dreams and plans. I offered to rent the knitting factory for a year and buy it (I prayed) thereafter. I didn’t hear back for a month, and I thought I’d have to keep looking.

But then he emailed me, and he told me he was interested. We met over video, across edges of the Atlantic Ocean, from my little Irish cottage to his sunny Florida home.

And he agreed to my offer. In fact, he told me he loved my project, and he wanted the knitting factory to go to someone who’d do right by it.

So here I am, every day, trying to do right. I am still raising my toddler, still working multiple jobs. I started a crowdfund that met its first goal within three days, and is now more than halfway to a down payment on a mortgage. And I am writing my book the exact same way I knit: word by word, stitch by stitch. Sometimes slower than I’d like, but every word, every stitch — even the mistakes I have to undo — a vital part of the finished whole.

I learned to knit when I was about eight years old, and knitting has always brought me a feeling of flexible strength that I can hold, and make, in my hands. When I was pregnant, I knit a stuffed dragon for my baby. When my marriage was unraveling, I knit a color-gradient shawl, from light to dark, that still feels like a security blanket on my shoulders. And when I was terrified of being separated from my child, I cut my baby’s outgrown onesies into long strips and knitted them together with my old shirts into a rug, thick and stiff. Something we could stand on.

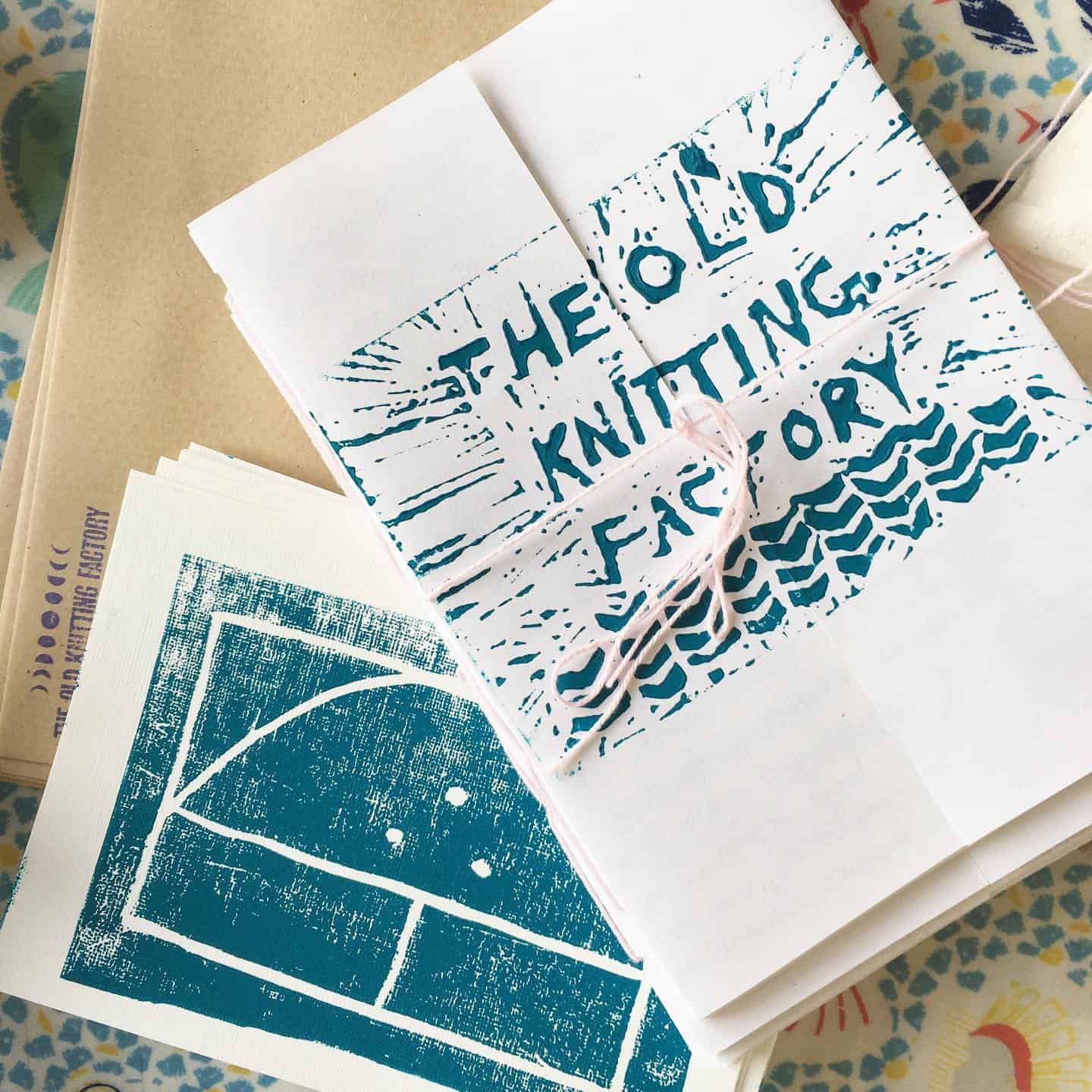

That rug lies on the floor of the knitting factory now. And I am working on something new: a knitting pattern I’ve designed myself. It’s still a work in progress, like the house, like the book. I’ve taken up embroidery, my friend Joan’s favorite craft, too, and I’m sewing the names of every crowdfund supporter into a tapestry that will hang on the factory wall. I hope to buy the factory this summer, and to start welcoming artists to the residency space as soon as the pandemic subsides enough to make such things safe again. I’m planning to prioritize artists who work in the genres that the building has housed before: knitters and fiber artists first, and then filmmakers, jewelry makers, and writers like me.

This project isn’t finished yet. Sometimes I wish I could finish it faster. But like writing a book, or knitting a blanket, I know that the most joy is found in the making.

Click here to support the crowdfunding campaign for The Old Knitting Factory.

Betsy Cornwell is a New York Times bestselling author living in west Ireland. She is the story editor and a contributing writer at Parabola, and her short-form writing includes fiction, nonfiction, and literary translation and has appeared in Fairy Tale Review, Zahir Tales, Luna Luna and elsewhere. She teaches fiction writing at the National University of Ireland and at writing retreats in Kylemore Abbey. Betsy’s new novel Reader, I Murdered Him, a queer romance and revenge sequel to Jane Eyre, will be published on September 21, 2021.

2 Responses

If you’ve been seeking a way to effectively promote the online business for sale, be sure to follow a few important insights from here for your deal to get resolved favorably with decent outcomes ultimately. Don’t ignore the suggestions provided to be satisfied with future results.

If you need support, whether for managing listings, accessing account features, or troubleshooting, check out rightmove plus. Their customer support team can assist with platform navigation, account settings, or technical difficulties. Ensure you have your login information or account reference ready for faster assistance.